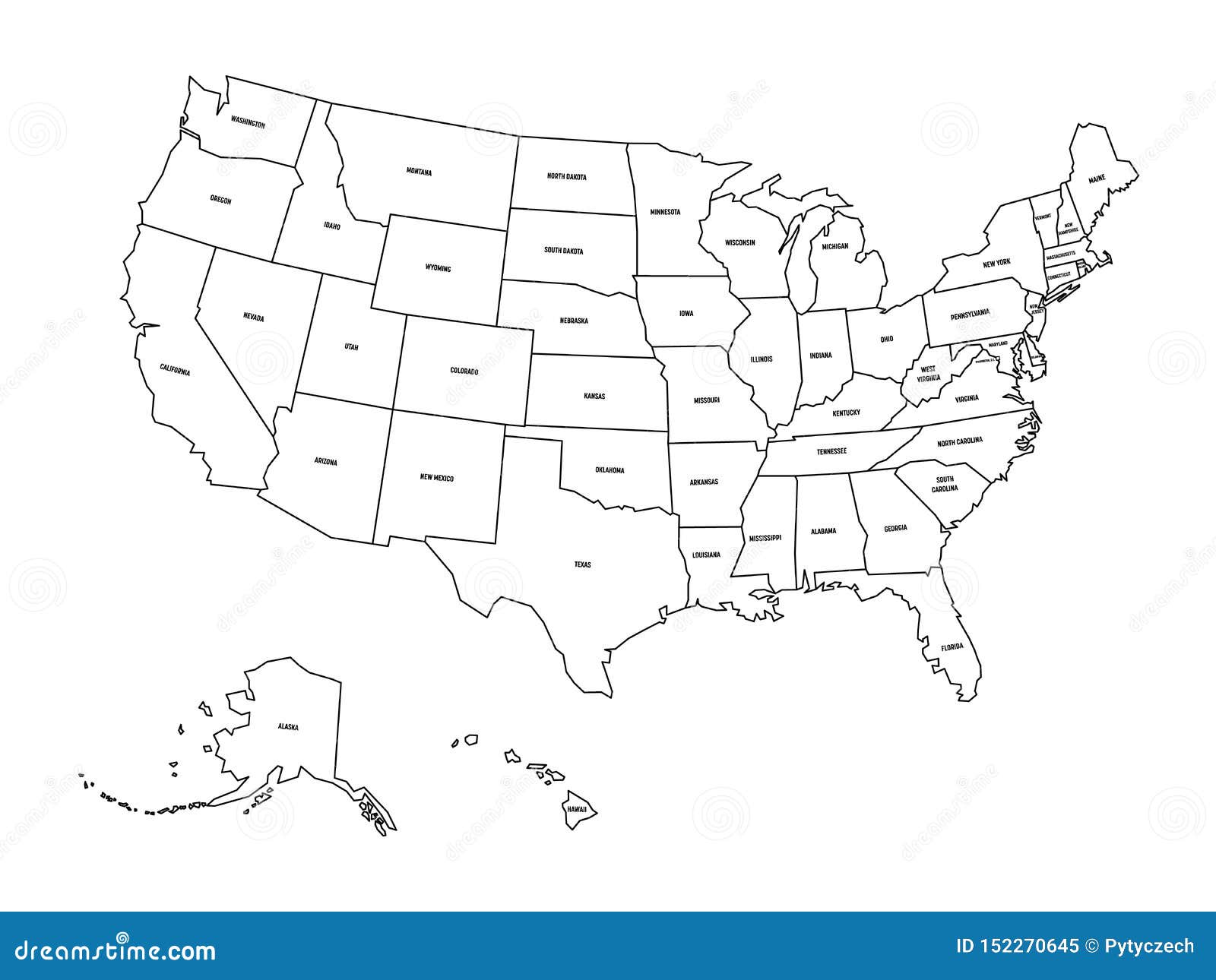

A map of the United States, stripped bare of names, is a disquieting thing. Familiar coastlines, mountain ranges, and river systems remain, but the anchors of identity – the city names, state borders, and landmarks etched into our collective consciousness – are gone. This “no names” map isn’t just a cartographic exercise; it’s a powerful tool for understanding the underlying geography, the historical forces that shaped the nation, and the profound impact of human intervention on the natural world. It forces us to engage with the land itself, to look beyond the labels and appreciate the complex tapestry woven by geology, climate, and human endeavor.

At first glance, the no names map presents a challenge. We are accustomed to navigating the US through a framework of place names, using them as mental shortcuts to identify regions and understand their significance. Without these familiar markers, our attention is immediately drawn to the physical geography. The stark contrast between the jagged peaks of the Rocky Mountains and the flat expanse of the Great Plains becomes more pronounced. The meandering path of the Mississippi River, carving its way through the heartland, stands out as a defining feature. The delicate tendrils of the Appalachian Mountains, stretching along the eastern seaboard, whisper tales of ancient geological formations.

The map reveals the fundamental role geography has played in shaping the distribution of population and industry. The absence of city names forces us to deduce their locations based on geographical features. We can infer that major urban centers likely cluster around natural harbors, navigable rivers, or fertile plains. The concentration of development along the eastern coastline, a consequence of early European settlement and access to maritime trade, becomes readily apparent. Similarly, the sparse population density in the arid regions of the Southwest underscores the limitations imposed by water scarcity and challenging terrain.

The no names map also highlights the impact of human intervention on the landscape. While the natural features remain, the imprint of human activity is undeniable, even without the aid of labels. The vast agricultural landscapes of the Midwest, characterized by a grid-like pattern of fields, speak to the transformative power of industrial agriculture. The network of highways, arteries of commerce and connection, snake across the map, reflecting the nation’s commitment to transportation infrastructure. The presence of large-scale dams and reservoirs, often visible as expansive bodies of water, underscores the efforts to control and harness water resources.

Consider the significance of the Mississippi River, a lifeline for the nation and a defining feature of the North American continent. Without the names of cities like St. Louis, Memphis, and New Orleans, the river’s importance as a transportation corridor and agricultural resource becomes even more evident. Its delta, a vast network of waterways and wetlands, stands as a testament to the power of natural processes and the challenges of managing a dynamic and ever-changing environment. The map invites us to ponder the river’s role in shaping the nation’s history, from the early days of steamboat travel to the modern era of barge traffic and agricultural irrigation.

The Rocky Mountains, a formidable barrier to westward expansion, present a different perspective. Without the names of iconic peaks and national parks, the sheer scale and ruggedness of the mountain range become the focal point. We are forced to contemplate the challenges faced by early pioneers crossing these mountains, the strategic importance of mountain passes, and the enduring allure of the wilderness. The presence of mining operations, often visible as scars on the landscape, reminds us of the economic forces that drove westward expansion and the environmental consequences of resource extraction.

The eastern coastline, with its complex network of bays, inlets, and islands, offers a glimpse into the nation’s maritime history. Without the names of coastal cities like Boston, New York, and Charleston, the importance of seaborne trade and maritime industries becomes more apparent. The concentration of population along the coast reflects the historical reliance on fishing, shipbuilding, and international commerce. The vulnerability of coastal communities to rising sea levels and extreme weather events, a pressing concern in the face of climate change, is also underscored by the map’s depiction of low-lying coastal areas.

The Great Plains, a vast expanse of grassland stretching across the heartland, presents a unique challenge to interpretation. Without the names of agricultural centers like Omaha and Kansas City, the region’s dependence on agriculture becomes the dominant theme. The presence of irrigation systems, visible as networks of canals and pipelines, underscores the efforts to overcome water scarcity and maximize agricultural productivity. The map invites us to consider the environmental impacts of intensive agriculture, including soil erosion, water depletion, and the loss of biodiversity.

Looking at the map, the absence of state borders is particularly striking. We are so accustomed to dividing the United States into neat political units that the removal of these boundaries forces us to see the country as a more unified whole. The underlying geography, the interconnectedness of river systems, and the shared history of the nation become more apparent. The map invites us to consider the arbitrary nature of political boundaries and the ways in which they can both unite and divide communities.

The no names map also encourages us to think about the concept of place itself. What makes a place significant? Is it the name, the history, the culture, or the physical environment? The map suggests that all of these factors are intertwined, but that the physical environment is the foundation upon which all other aspects of place are built. Without the names, we are forced to confront the raw, unadorned landscape and to appreciate its intrinsic value.

Furthermore, the map compels us to reconsider our relationship with the land. In a society increasingly disconnected from the natural world, the no names map offers a powerful reminder of our dependence on the environment. It forces us to think about the resources we consume, the waste we generate, and the impact we have on the planet. By removing the familiar landmarks and place names, the map strips away the layers of abstraction that often obscure our understanding of environmental issues.

In conclusion, a map of the United States without names is more than just a blank slate. It is a powerful tool for understanding the geography, history, and human impact on the American landscape. It forces us to look beyond the labels and appreciate the complex interplay of natural forces and human endeavor. It invites us to reconsider our relationship with the land and to reflect on the meaning of place. By stripping away the familiar markers of identity, the no names map reveals the silent landscape beneath, a landscape that holds the key to understanding the past, present, and future of the United States. It’s a reminder that even without the labels, the story of America is etched into the land itself, waiting to be read by those who take the time to look. The map becomes a canvas for our own understanding, a space for projecting our knowledge and assumptions, and ultimately, for gaining a deeper appreciation for the complex and beautiful tapestry that is the United States of America.