Shingles, a painful and often debilitating condition, is a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the same virus that causes chickenpox. While many associate it with a childhood illness, VZV can lie dormant in the body for decades, only to re-emerge as shingles, causing a characteristic rash and pain along specific nerve pathways. Understanding the dermatome map, a crucial tool in diagnosing and managing shingles, is essential for both medical professionals and those affected by this common ailment.

What is Shingles? A Recurrence of a Childhood Foe

After a bout of chickenpox, the VZV virus doesn’t disappear entirely. Instead, it retreats to nerve cells near the spinal cord and brain, where it remains inactive. In many individuals, the virus stays dormant for life. However, in others, particularly those with weakened immune systems, the virus can reactivate. This reactivation manifests as shingles, characterized by a painful, blistering rash that typically appears on one side of the body.

The precise reason for VZV reactivation remains unclear, but several factors are believed to contribute, including:

- Age: The risk of shingles increases with age, especially after 50.

- Weakened Immune System: Conditions that compromise the immune system, such as HIV/AIDS, cancer, or certain medications (immunosuppressants), increase the likelihood of reactivation.

- Stress: Periods of significant stress can sometimes trigger shingles.

- Certain Medical Conditions: Some chronic illnesses may also increase the risk.

The Role of Dermatomes: Mapping the Nerve Landscape

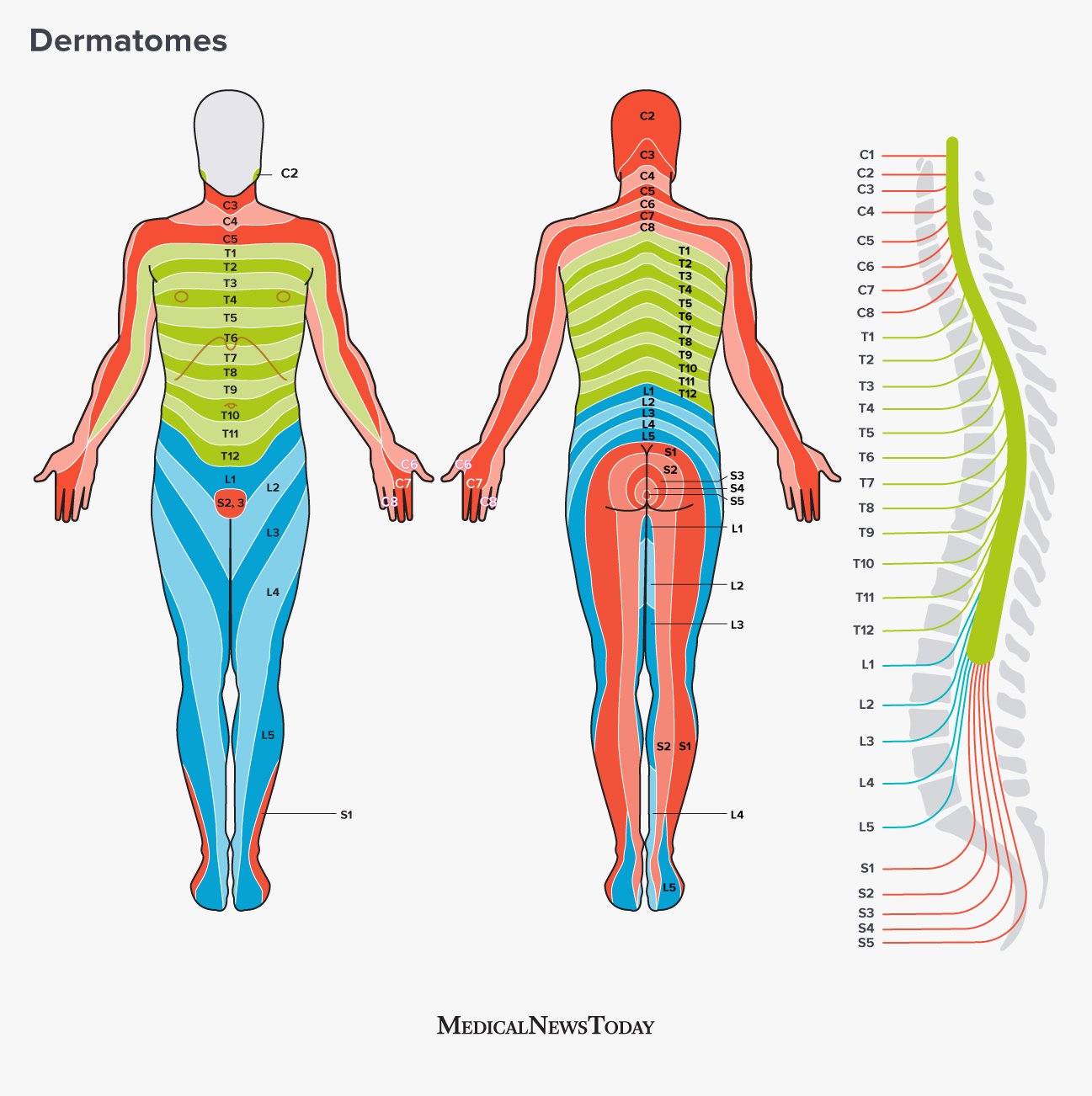

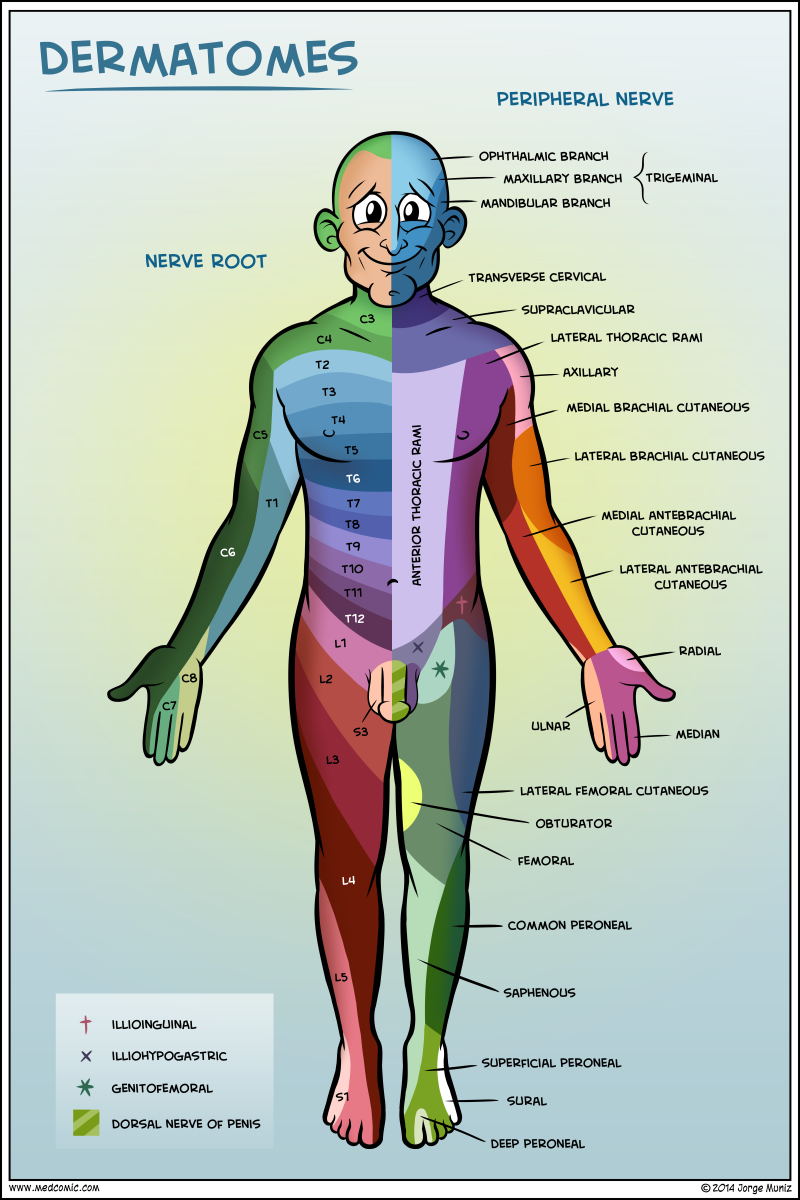

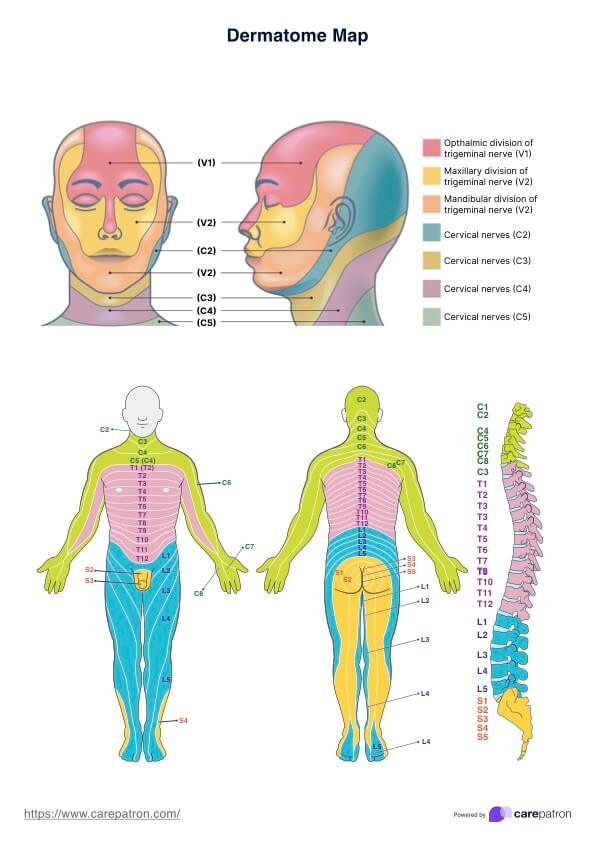

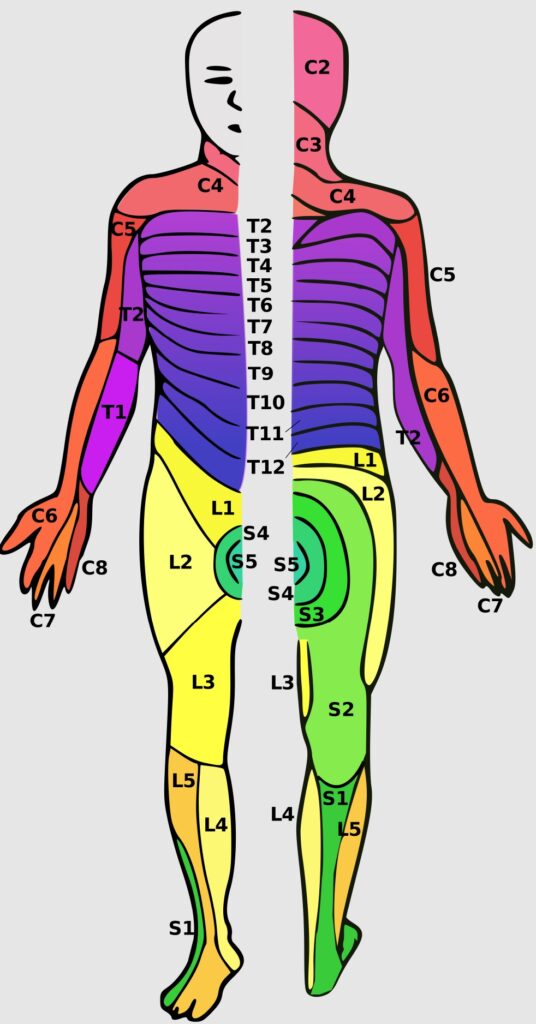

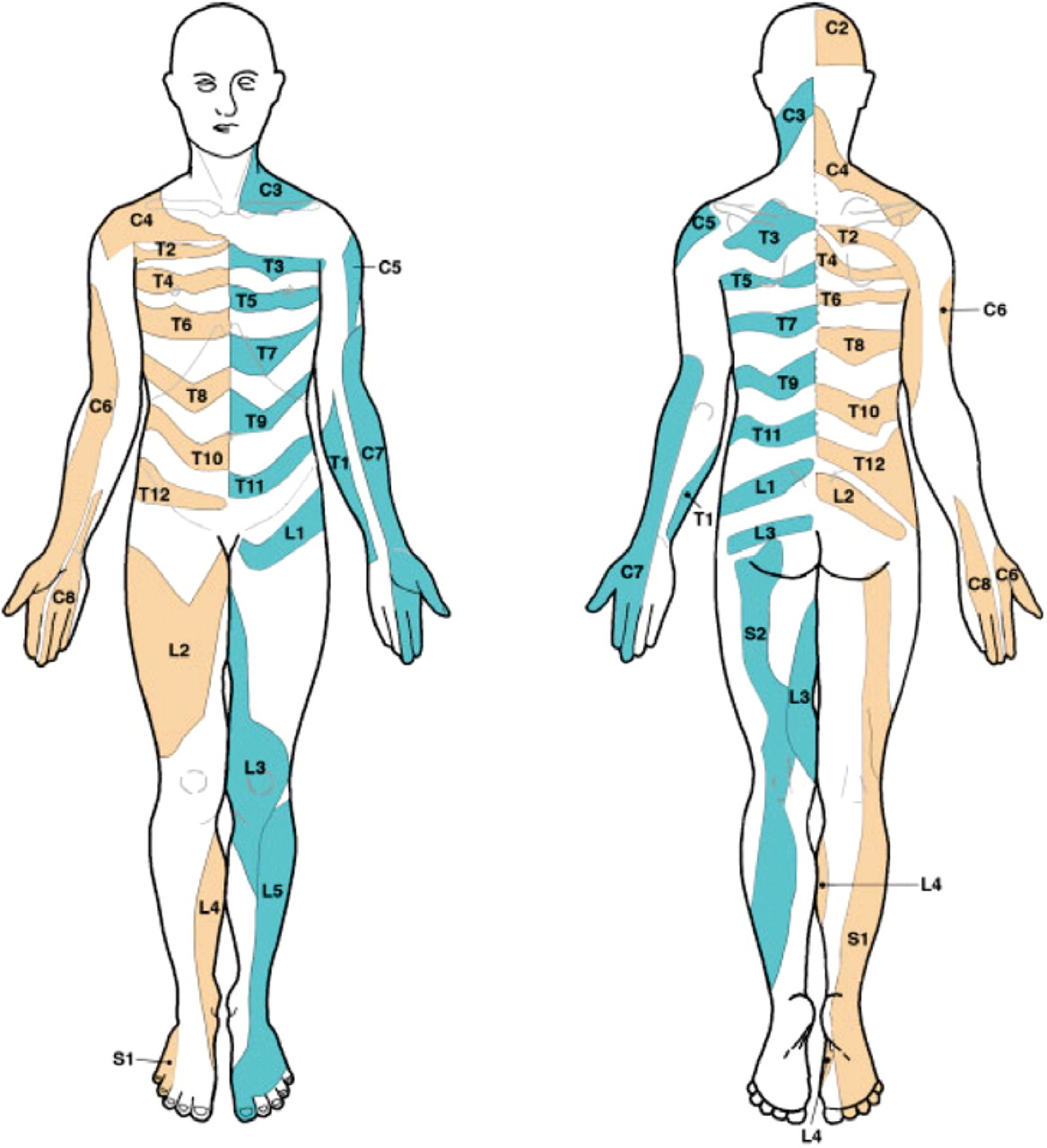

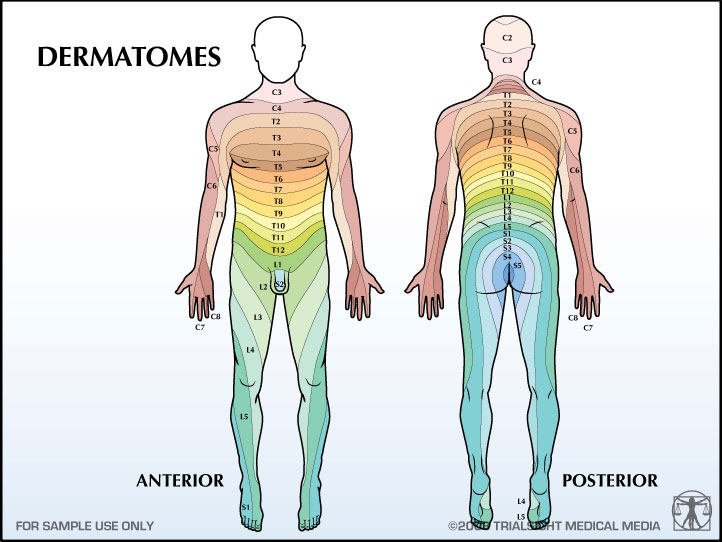

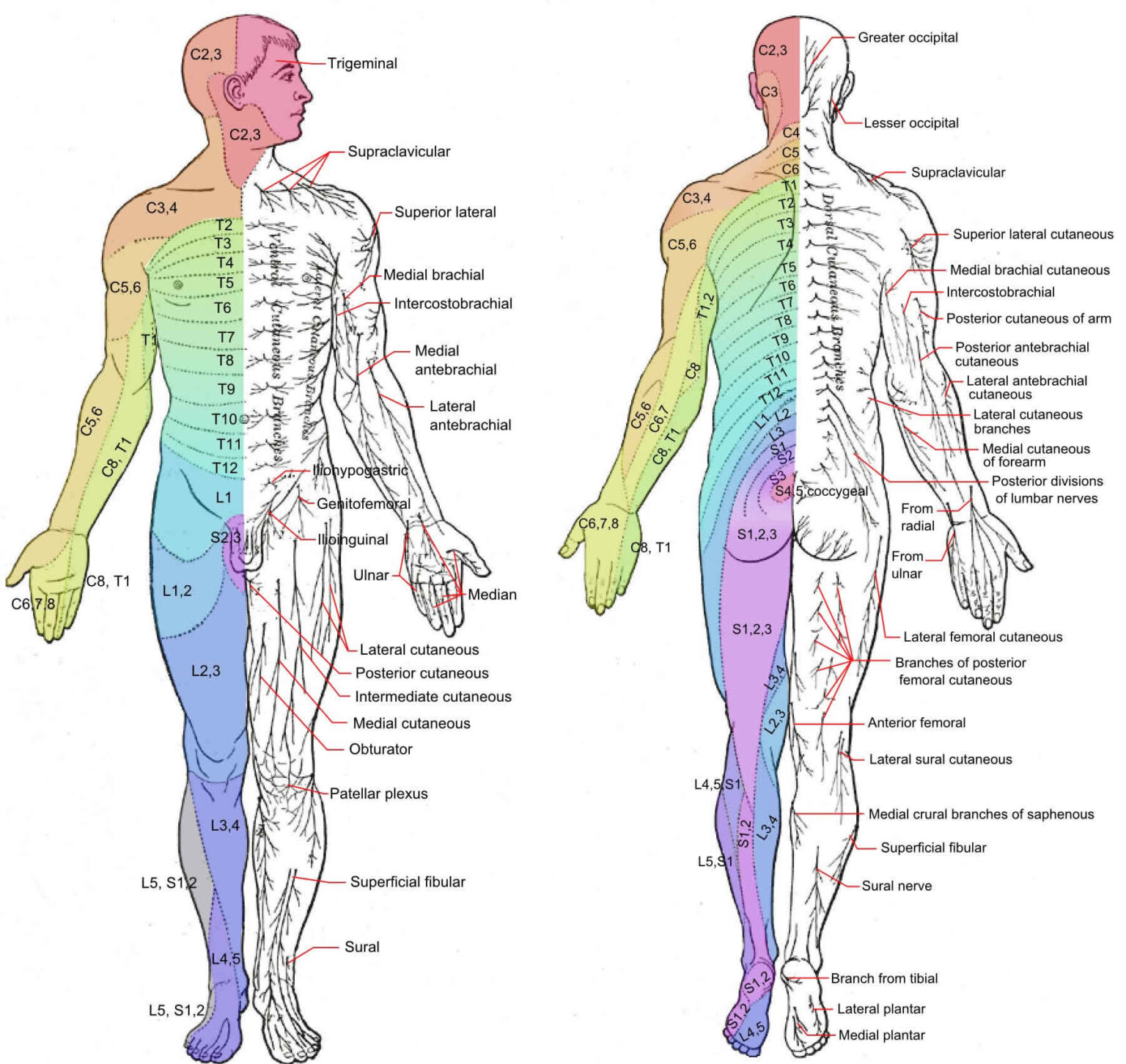

To understand shingles, it’s vital to grasp the concept of dermatomes. A dermatome is an area of skin that is supplied by a single spinal nerve. Each spinal nerve exits the spinal cord and innervates a specific region of the body, forming a distinct dermatome. These dermatomes are arranged in a predictable pattern, creating a "map" of sensory innervation across the skin.

Imagine the human body divided into strips or bands, each corresponding to a specific spinal nerve. This is essentially what the dermatome map illustrates. The map provides a visual representation of which nerve root supplies sensation to which area of skin.

The Dermatome Map and Shingles: A Direct Connection

The dermatome map is crucial in understanding and diagnosing shingles because the rash typically follows the path of a single dermatome. When VZV reactivates, it travels along the nerve fibers associated with a specific spinal nerve. This explains why the shingles rash is almost always unilateral (appearing on only one side of the body) and confined to a particular region corresponding to the affected dermatome.

The most commonly affected dermatomes in shingles are those in the thoracic region (chest and abdomen), followed by the cervical region (neck and shoulders) and the trigeminal nerve (face). Less frequently, shingles can affect the lumbar region (lower back and legs) or the sacral region (buttocks and genitals).

Identifying Shingles Using the Dermatome Map

The characteristic rash of shingles, combined with the patient’s description of pain or tingling in a specific area, often leads to a diagnosis based on the dermatome map. Here’s how the map aids in identification:

- Location of the Rash: The location of the rash is the most important clue. By comparing the rash’s distribution to the dermatome map, healthcare professionals can identify the specific spinal nerve involved.

- Unilateral Distribution: Shingles almost always affects only one side of the body, aligning with the innervation pattern of a single spinal nerve.

- Pain and Sensory Changes: Before the rash appears, many individuals experience pain, tingling, itching, or burning in the affected dermatome. This pre-eruptive phase can last for several days and can be difficult to diagnose without considering the dermatome pattern.

- Blister Formation: The rash typically begins as small, red bumps that quickly develop into fluid-filled blisters (vesicles). These blisters often cluster together and eventually break, forming scabs.

Common Dermatome Patterns in Shingles

While shingles can affect any dermatome, certain patterns are more common:

- Thoracic Dermatomes (T3-T12): This is the most frequent location for shingles, often presenting as a band of rash and pain around the chest or abdomen.

- Cervical Dermatomes (C2-C8): Shingles affecting the cervical dermatomes can cause pain and rash in the neck, shoulder, arm, and hand.

- Trigeminal Nerve (V1, V2, V3): When the trigeminal nerve is involved, shingles can affect the forehead (V1), cheek and upper jaw (V2), or lower jaw (V3). Ophthalmic shingles (affecting the V1 branch) can be particularly serious, potentially leading to vision problems.

- Lumbar Dermatomes (L1-L5): Shingles in the lumbar region can cause pain and rash in the lower back, buttocks, and legs.

- Sacral Dermatomes (S1-S5): Sacral shingles can affect the genitals, buttocks, and inner thighs, potentially leading to bowel or bladder dysfunction in rare cases.

Treatment and Management of Shingles

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for minimizing the severity and duration of shingles and reducing the risk of complications. Treatment typically involves:

- Antiviral Medications: Antiviral drugs like acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are most effective when started within 72 hours of the rash appearing. These medications help to reduce viral replication, shorten the duration of the illness, and lessen the severity of symptoms.

- Pain Management: Pain management is a key aspect of shingles treatment. Over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen can provide relief for mild pain. For more severe pain, prescription pain medications, such as opioids or nerve pain medications (gabapentin or pregabalin), may be necessary.

- Topical Treatments: Topical creams or lotions, such as calamine lotion or capsaicin cream, can help to soothe the skin and relieve itching.

- Prevention of Secondary Infections: Keeping the rash clean and dry is essential to prevent secondary bacterial infections.

- Shingles Vaccine: The shingles vaccine (Shingrix) is highly effective in preventing shingles and its complications. It is recommended for adults aged 50 and older, even if they have had chickenpox or shingles before.

Complications of Shingles

While most individuals recover fully from shingles, complications can occur, including:

- Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN): PHN is the most common complication of shingles. It is characterized by persistent nerve pain in the area affected by the rash, even after the rash has healed. PHN can be debilitating and difficult to treat.

- Ophthalmic Shingles: Shingles affecting the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve can lead to vision loss, corneal damage, and other eye problems. Prompt treatment by an ophthalmologist is crucial.

- Bacterial Infections: The shingles rash can become infected with bacteria, requiring antibiotic treatment.

- Neurological Complications: In rare cases, shingles can lead to neurological complications such as encephalitis (brain inflammation) or meningitis (inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord).

The Importance of Vaccination

The best way to prevent shingles and its complications is through vaccination. The Shingrix vaccine is highly effective in preventing shingles and is recommended for adults aged 50 and older. Vaccination significantly reduces the risk of developing shingles and, if shingles does occur, it tends to be milder and less likely to lead to complications like PHN.

Conclusion

Shingles can be a painful and debilitating condition, but understanding the role of dermatomes in its presentation is key to accurate diagnosis and effective management. The dermatome map provides a vital framework for healthcare professionals to identify the affected nerve and tailor treatment accordingly. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with antiviral medications and pain management strategies can significantly improve outcomes and reduce the risk of complications. Furthermore, vaccination with the Shingrix vaccine offers a highly effective means of preventing shingles and protecting against its potential long-term consequences. By understanding the intricacies of shingles and the importance of the dermatome map, we can better manage this common condition and improve the quality of life for those affected.