In the realm of psychology, understanding how we perceive, represent, and navigate the world around us is a fundamental pursuit. Central to this understanding is the concept of the cognitive map, a mental representation of our environment that allows us to orient ourselves, plan routes, and make informed decisions about spatial relationships. Far from being a simple, photographic memory of our surroundings, the cognitive map is a dynamic, multifaceted construct shaped by experience, perception, and individual biases. This article delves into the definition, development, function, and significance of cognitive maps in psychology, exploring their influence on behavior, learning, and even our emotional well-being.

Defining the Cognitive Map: A Mental Representation of Space

The term "cognitive map" was first coined by psychologist Edward Tolman in 1948, based on his groundbreaking research with rats navigating mazes. Tolman observed that rats, after repeated exposure to a maze, didn’t just learn a series of rote turns; they developed an internal, holistic representation of the maze layout. This mental representation, he argued, allowed them to find novel shortcuts and adapt to changes in the maze environment, suggesting a more sophisticated understanding of spatial relationships than simple stimulus-response learning.

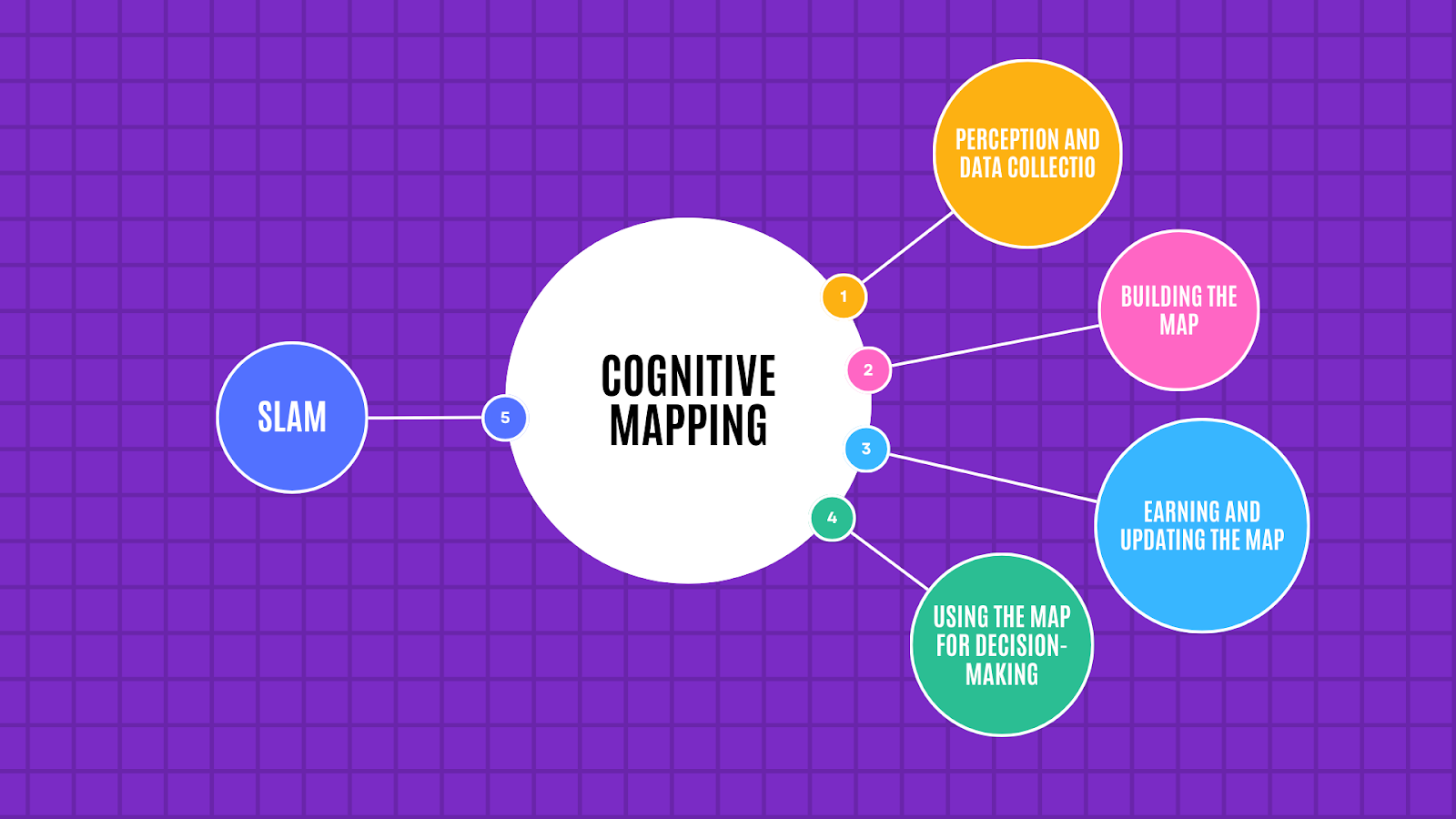

In essence, a cognitive map is a mental model of the spatial environment. It encompasses not just physical landmarks and routes, but also relationships between these elements, creating a comprehensive, albeit subjective, understanding of the space. This mental representation can include information about:

- Landmarks: Distinctive features of the environment, such as buildings, parks, or even specific trees.

- Routes: Sequences of actions and landmarks required to navigate between locations.

- Distances: Perceived or estimated distances between different points in the environment.

- Angles and Directions: The relative spatial orientation of different locations.

- Spatial Relationships: The connections and proximities between various elements in the environment.

Crucially, cognitive maps are not merely passive records of the environment; they are actively constructed and constantly updated through experience. They are influenced by our perceptions, memories, and individual biases, leading to highly personalized and often imperfect representations of the world.

The Development of Cognitive Maps: From Egocentric to Allocentric

The development of cognitive maps is a gradual process that begins in infancy and continues throughout life. Initially, infants rely on egocentric representations, understanding their environment in relation to their own bodies. They learn to associate specific actions (e.g., turning left) with particular outcomes (e.g., reaching a toy). This egocentric understanding is limited, as it is tied to the individual’s current position and perspective.

As children grow, they begin to develop allocentric representations, which are independent of their own location and perspective. They learn to understand spatial relationships between objects and locations, regardless of their own position. This shift from egocentric to allocentric representations is crucial for developing a robust and flexible cognitive map.

Several factors contribute to the development of allocentric cognitive maps:

- Exploration and Experience: Actively exploring the environment is essential for building a comprehensive cognitive map. The more we interact with a space, the more detailed and accurate our mental representation becomes.

- Landmark Recognition and Association: Identifying and remembering landmarks is a crucial step in building a cognitive map. As we explore, we associate landmarks with each other and with specific locations, forming a network of spatial relationships.

- Language and Spatial Reasoning: Language plays a vital role in the development of cognitive maps. Learning spatial terms (e.g., "left," "right," "north," "south") and understanding spatial concepts (e.g., "distance," "direction," "relative position") helps us to organize and structure our mental representations.

- Perspective Taking: The ability to imagine oneself in a different location and perspective is crucial for understanding allocentric relationships. As children develop perspective-taking skills, they become better at understanding how different locations relate to each other, regardless of their own position.

Functions of Cognitive Maps: Guiding Navigation and Decision-Making

Cognitive maps serve a variety of important functions in our daily lives, allowing us to navigate, plan, and make informed decisions about our environment. Some key functions include:

- Navigation: Cognitive maps enable us to navigate efficiently and effectively, even in unfamiliar environments. By accessing our mental representation of the space, we can plan routes, anticipate obstacles, and adapt to unexpected changes.

- Wayfinding: Wayfinding involves the process of finding our way to a desired location, often in a complex or unfamiliar environment. Cognitive maps provide the foundation for wayfinding by allowing us to understand the spatial relationships between our current location, our destination, and other relevant landmarks.

- Spatial Problem Solving: Cognitive maps allow us to solve spatial problems, such as finding the shortest route between two points or determining the best location for a new business. By mentally manipulating our representation of the environment, we can explore different possibilities and make informed decisions.

- Spatial Reasoning: Cognitive maps support spatial reasoning, which involves the ability to understand and manipulate spatial relationships. This ability is essential for a wide range of tasks, including reading maps, assembling furniture, and understanding architectural designs.

- Planning and Decision-Making: Cognitive maps influence our planning and decision-making processes by providing a framework for understanding the potential consequences of our actions. For example, when deciding whether to take a particular route, we can use our cognitive map to estimate the distance, time, and potential obstacles involved.

Significance of Cognitive Maps: Impact on Behavior, Learning, and Well-being

The concept of the cognitive map has had a profound impact on our understanding of human behavior, learning, and well-being. Its significance extends across various fields, including:

- Psychology: Cognitive maps have been instrumental in understanding spatial cognition, navigation, and learning. They have provided insights into how we represent and process spatial information, and how this information influences our behavior.

- Education: Understanding how cognitive maps develop can inform educational strategies aimed at improving spatial reasoning and navigation skills. Incorporating activities that encourage exploration, landmark recognition, and spatial problem-solving can enhance children’s ability to build robust cognitive maps.

- Architecture and Urban Planning: Architects and urban planners use principles of cognitive mapping to design environments that are easy to navigate and understand. By creating clear landmarks, intuitive layouts, and well-defined routes, they can enhance the user experience and promote a sense of orientation and safety.

- Neuroscience: Neuroscience research has identified specific brain regions involved in the formation and retrieval of cognitive maps, including the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. These regions are crucial for spatial memory, navigation, and the representation of spatial relationships.

- Human-Computer Interaction: Cognitive maps are relevant to the design of user interfaces for navigation systems and virtual environments. By understanding how users mentally represent space, designers can create interfaces that are intuitive, efficient, and effective.

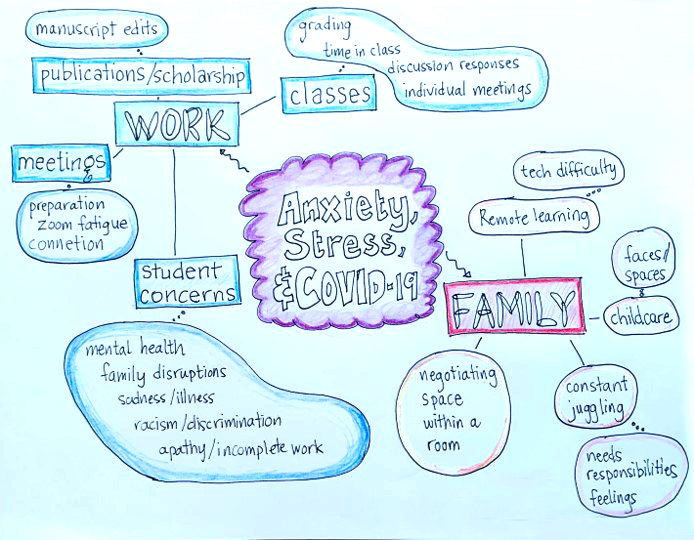

- Mental Health: Research suggests that impairments in cognitive mapping can contribute to anxiety and disorientation, particularly in individuals with conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease or agoraphobia. Understanding the link between cognitive maps and mental health can inform interventions aimed at improving spatial orientation and reducing anxiety.

Challenges and Future Directions:

Despite significant advancements, understanding cognitive maps remains a complex and ongoing endeavor. Several challenges and future directions warrant further investigation:

- Individual Differences: Cognitive mapping abilities vary significantly among individuals. Understanding the factors that contribute to these differences, such as age, gender, experience, and cognitive style, is crucial for developing personalized interventions and educational strategies.

- Influence of Technology: The increasing reliance on GPS and other navigation technologies may be affecting our ability to develop and maintain robust cognitive maps. Investigating the impact of technology on spatial cognition is essential for understanding the long-term consequences of our digital dependence.

- Dynamic Environments: Most research on cognitive maps has focused on relatively static environments. Understanding how cognitive maps adapt to dynamic and changing environments, such as cities undergoing rapid development, is a crucial area for future research.

- Emotional Influences: The relationship between emotions and cognitive maps is complex and not fully understood. Investigating how emotions influence our perception of space, our ability to navigate, and our overall spatial experience is an important area for future research.

Conclusion:

The cognitive map is a fundamental concept in psychology that provides valuable insights into how we perceive, represent, and navigate the world around us. This mental representation of space allows us to orient ourselves, plan routes, make informed decisions, and even experience a sense of belonging and connection to our environment. Understanding the development, function, and significance of cognitive maps is crucial for a wide range of fields, from education and architecture to neuroscience and mental health. As we continue to explore the complexities of the human mind, the cognitive map will undoubtedly remain a central focus of research and a powerful tool for understanding our relationship with the world.