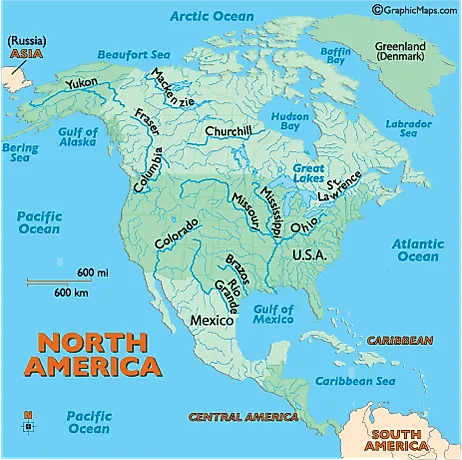

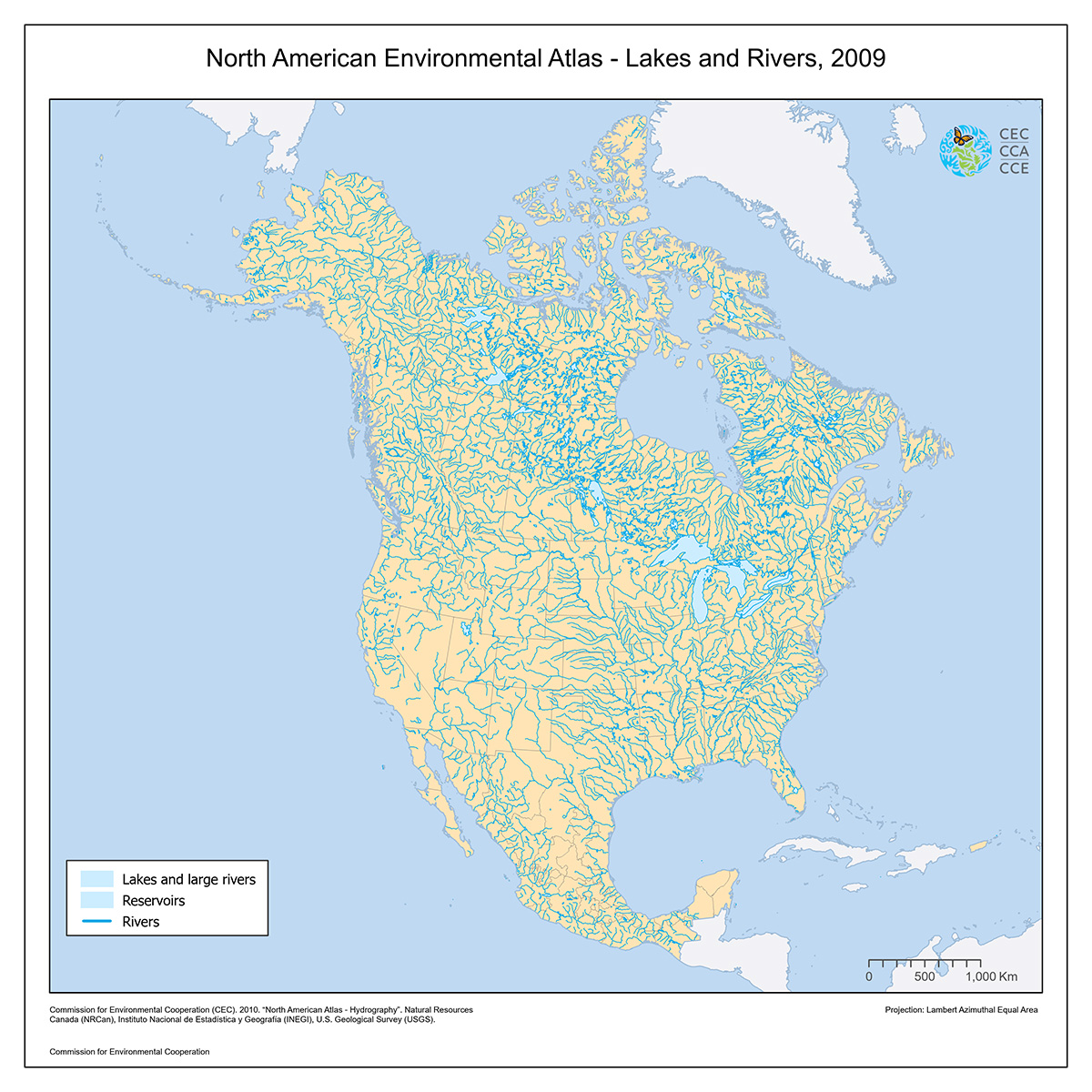

North America, a continent sculpted by time and the relentless force of water, boasts a complex and fascinating network of rivers. These arteries of life have shaped the landscape, dictated settlement patterns, and fueled economies for millennia. Understanding the rivers of North America, their courses, their significance, and their challenges, provides a crucial lens through which to view the continent’s history, ecology, and future. A comprehensive rivers of North America map offers a visual journey through this vital hydrological system, revealing the interconnectedness of the land and the water that sustains it.

The Grand Divides: Dividing the Waters

Before delving into specific river systems, it’s essential to grasp the concept of continental divides. These elevated ridges of land determine the direction in which rivers flow. North America features three major continental divides:

- The Great Divide (Continental Divide): The most prominent, running along the crest of the Rocky Mountains. Rivers east of this divide generally flow towards the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, or the Arctic Ocean. Rivers west of the divide drain into the Pacific Ocean.

- The Laurentian Divide: Located in eastern Canada, this divide separates rivers flowing into the Atlantic Ocean from those flowing into Hudson Bay and the Arctic Ocean.

- The Arctic Divide: This divide separates the Arctic Ocean drainage basin from the Hudson Bay and Atlantic Ocean basins.

Understanding these divides is crucial to interpreting the rivers of North America map. They explain why certain rivers flow in specific directions and why river systems on either side of a divide may have vastly different characteristics.

Iconic Rivers of the United States:

The United States is crisscrossed by a vast network of rivers, each with its unique history and ecological importance. Some of the most prominent include:

-

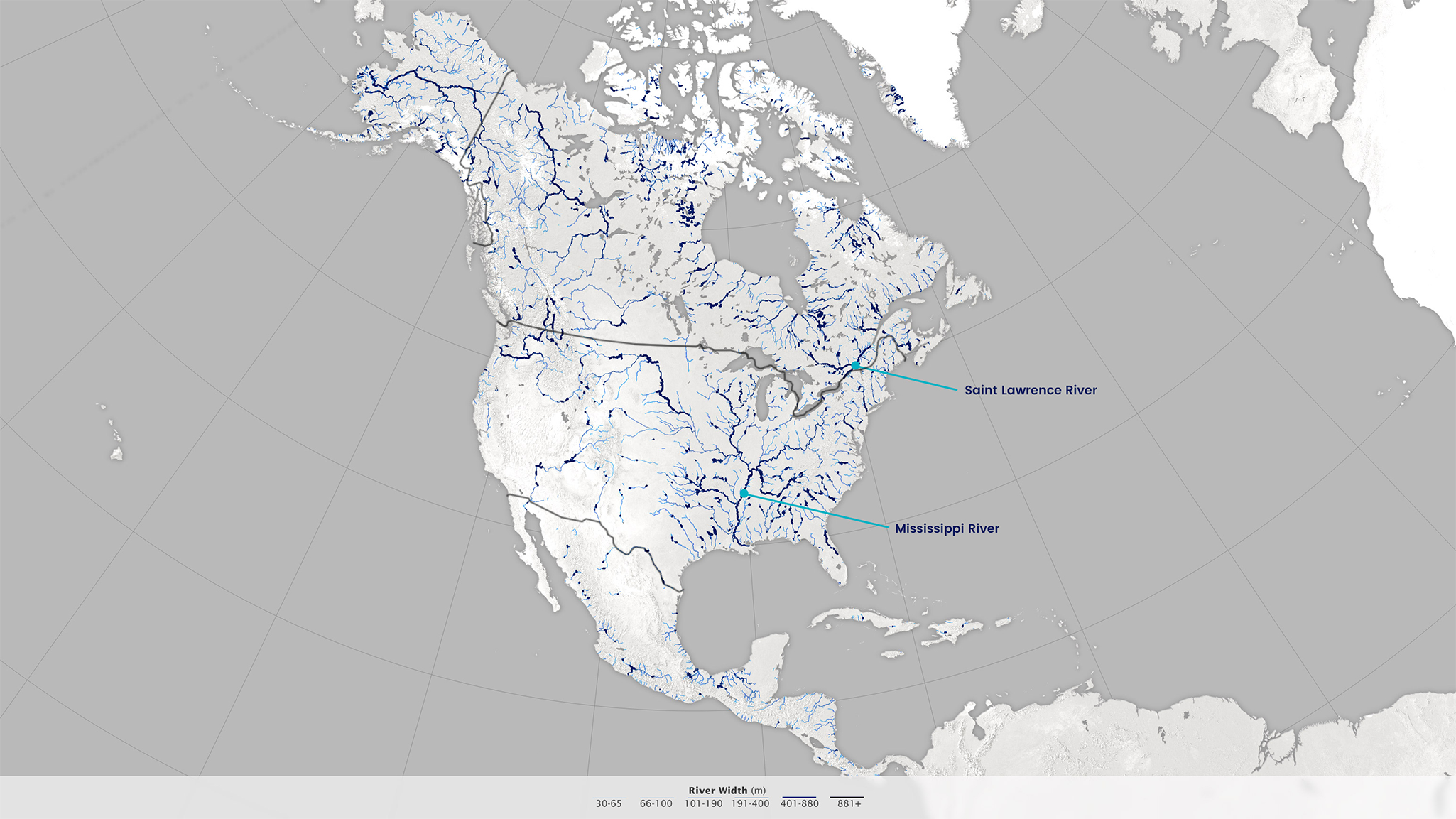

The Mississippi River: The undisputed king of North American rivers, the Mississippi is the second-longest river on the continent and the fourth-longest in the world. Its vast drainage basin encompasses 41% of the contiguous United States, collecting water from tributaries like the Missouri, Ohio, Arkansas, and Red Rivers. The Mississippi has been a crucial transportation route for centuries, connecting the agricultural heartland to the Gulf of Mexico and facilitating trade. However, its management has become a complex challenge, with issues ranging from flood control and navigation to agricultural runoff and the Dead Zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

-

The Missouri River: The longest river in North America, the Missouri flows for over 2,300 miles from its source in the Rocky Mountains to its confluence with the Mississippi River near St. Louis. The Missouri played a pivotal role in westward expansion, serving as a major transportation corridor for explorers, fur traders, and settlers. Today, it is dammed extensively for flood control, irrigation, and hydropower, significantly altering its natural flow regime.

-

The Colorado River: Carving its way through the arid landscapes of the American Southwest, the Colorado River is a lifeline for millions of people. Its water is essential for agriculture, urban development, and recreation in the region. However, the Colorado River is also one of the most heavily managed and over-allocated rivers in the world. Decades of overuse have led to dwindling flows and increasing conflicts over water rights, particularly as climate change intensifies the region’s drought conditions. The Colorado River is a stark example of the challenges of balancing human needs with the ecological health of a river system.

-

The Columbia River: A powerful river flowing through the Pacific Northwest, the Columbia is renowned for its salmon runs and its hydroelectric power potential. Numerous dams have been built along the Columbia, generating significant amounts of electricity but also impacting salmon populations and altering the river’s natural flow. Balancing hydropower production with the restoration of salmon runs is a major environmental challenge in the Columbia River basin.

-

The Rio Grande: Forming a significant portion of the border between the United States and Mexico, the Rio Grande is a vital water source for both countries. However, the river is facing severe water scarcity issues due to overuse, drought, and climate change. International cooperation is crucial to manage the Rio Grande sustainably and ensure its continued role in supporting communities on both sides of the border.

Canadian Rivers: Flowing to the Arctic and Beyond:

Canada’s rivers are vast, wild, and largely untouched by extensive development. Many of them flow into the Arctic Ocean and Hudson Bay, reflecting the country’s northerly latitude. Key Canadian rivers include:

-

The Mackenzie River: The longest river system in Canada and the second-longest in North America, the Mackenzie flows north into the Arctic Ocean. Its vast drainage basin encompasses a large portion of northwestern Canada. The Mackenzie River is relatively undeveloped compared to rivers in the United States, but it is facing increasing pressures from resource extraction, particularly oil and gas development.

-

The St. Lawrence River: Forming a crucial waterway for trade and transportation, the St. Lawrence connects the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. The St. Lawrence Seaway allows ocean-going vessels to navigate deep into the heart of North America, making the river a vital economic artery. However, the St. Lawrence is also facing environmental challenges, including pollution and invasive species.

-

The Fraser River: Located in British Columbia, the Fraser River is renowned for its salmon runs and its scenic beauty. The Fraser River basin is a major source of timber and mineral resources, but these activities have also impacted the river’s ecosystem. Balancing resource development with environmental protection is a key challenge in the Fraser River basin.

-

The Nelson River: Draining a vast area of the Canadian Prairies, the Nelson River flows into Hudson Bay. The Nelson River is heavily dammed for hydroelectric power generation, significantly altering its natural flow regime. The impacts of these dams on downstream ecosystems are a subject of ongoing concern.

Mexican Rivers: Scarce Resources in a Dry Land:

Mexico’s rivers are generally smaller and more arid than those in the United States and Canada, reflecting the country’s climate and geography. Water scarcity is a major challenge in many parts of Mexico, making the sustainable management of its rivers crucial. Notable Mexican rivers include:

-

The Rio Bravo (Rio Grande): As mentioned earlier, the Rio Grande forms a significant portion of the border between the United States and Mexico. Its importance to both countries cannot be overstated.

-

The Grijalva River: Located in southeastern Mexico, the Grijalva River is one of the country’s largest and most important rivers. It is heavily dammed for hydroelectric power generation, supplying electricity to a large portion of the country.

-

The Usumacinta River: Forming part of the border between Mexico and Guatemala, the Usumacinta is the largest river in Central America. Its basin is rich in biodiversity and cultural heritage, but it is facing increasing pressures from deforestation, agriculture, and oil exploration.

Challenges and Future Considerations:

The rivers of North America are facing a multitude of challenges, including:

-

Climate Change: Changing precipitation patterns, increased temperatures, and more frequent droughts are impacting river flows and water availability across the continent.

-

Pollution: Agricultural runoff, industrial discharge, and urban wastewater are polluting rivers and harming aquatic ecosystems.

-

Over-Allocation: In many regions, rivers are over-allocated, meaning that more water is being withdrawn than is sustainably available.

-

Habitat Loss: Dams, diversions, and other infrastructure projects have altered river habitats and impacted fish populations.

-

Invasive Species: Invasive species are disrupting native ecosystems and impacting the health of rivers.

Addressing these challenges requires a collaborative and integrated approach that considers the needs of all stakeholders. Sustainable water management practices, such as water conservation, efficient irrigation techniques, and improved wastewater treatment, are essential to ensure the long-term health of North America’s rivers. International cooperation is also crucial, particularly for rivers that cross national borders.

Conclusion:

The rivers of North America are more than just lines on a map; they are vital lifelines that sustain ecosystems, economies, and communities. A comprehensive rivers of North America map provides a valuable tool for understanding the complex hydrological system of the continent and the challenges it faces. By appreciating the interconnectedness of these rivers and the importance of their sustainable management, we can work towards a future where these vital resources are protected for generations to come. Understanding the rivers of North America allows us to better understand the history, ecology, and future of the continent itself. They are, after all, the very veins that bring life to the land.