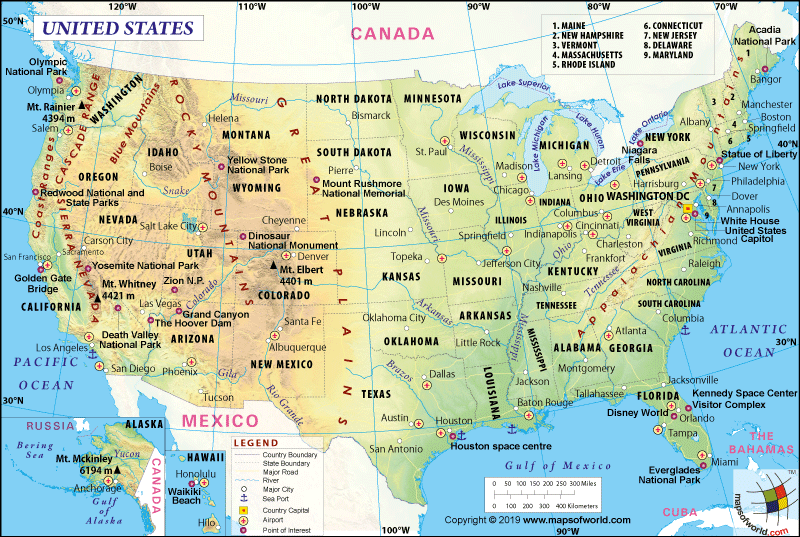

The United States, a land of sprawling landscapes and diverse ecosystems, owes much of its identity and prosperity to its intricate network of rivers. These waterways, often referred to as the nation’s veins, have shaped the physical geography, influenced settlement patterns, facilitated trade, and provided sustenance for centuries. Understanding the major rivers of the US, and their complex interplay, is crucial to grasping the nation’s history, economy, and environmental challenges. This article will explore the significance of these vital waterways, focusing on key rivers and their impact on the American tapestry.

The Mighty Mississippi: Father of Waters and Economic Lifeline

No discussion of US rivers is complete without acknowledging the Mississippi River. Deriving its name from the Ojibwe word "misi-ziibi" meaning "great river," the Mississippi reigns supreme as the longest river system in North America. Flowing approximately 2,320 miles from its source in Lake Itasca, Minnesota, to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico near New Orleans, Louisiana, the Mississippi and its tributaries drain a vast area encompassing 31 states, representing over 40% of the continental US.

The Mississippi’s historical significance is undeniable. Native American cultures thrived along its banks for millennia, utilizing it for transportation, fishing, and agriculture. European explorers, including Hernando de Soto and René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, recognized its strategic importance, claiming the river and its surrounding territory for Spain and France respectively. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 secured control of the Mississippi for the United States, opening up vast stretches of land for westward expansion and solidifying the nation’s economic power.

Today, the Mississippi remains a vital transportation artery, facilitating the movement of goods such as grain, coal, petroleum, and manufactured products. Barges navigate its waters, connecting agricultural heartlands to international markets. However, this intensive use has come at a cost. The river faces significant environmental challenges, including pollution from agricultural runoff, industrial discharge, and urban sewage. Efforts to restore the Mississippi River ecosystem are ongoing, aiming to balance economic needs with ecological sustainability.

The Missouri: The Longest River, A Vital Source of Irrigation

Often considered a tributary of the Mississippi, the Missouri River is actually longer, stretching approximately 2,341 miles from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains of Montana to its confluence with the Mississippi near St. Louis, Missouri. The Missouri River basin encompasses portions of ten states and plays a critical role in the agricultural productivity of the Great Plains.

The Missouri River, once known as the "Big Muddy" due to its sediment load, was a crucial pathway for westward expansion in the 19th century. Lewis and Clark famously traversed the Missouri in their expedition to explore the Louisiana Purchase, charting its course and documenting the flora, fauna, and indigenous cultures along its banks. Steamboats plied the Missouri, carrying settlers, supplies, and trade goods, fueling the growth of towns and cities along its route.

Today, the Missouri River is heavily dammed and regulated for flood control, irrigation, and hydroelectric power generation. Reservoirs like Lake Sakakawea and Lake Oahe provide water for agriculture and recreation. However, these dams have also altered the river’s natural flow, impacting fish populations and riparian ecosystems. Balancing the competing demands of water resources management remains a significant challenge for the Missouri River basin.

The Colorado: Carving Canyons and Quenching Thirst

The Colorado River, a relatively shorter river at approximately 1,450 miles, originates in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and flows southwestward through Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and California before emptying into the Gulf of California in Mexico. While not as long as the Mississippi or Missouri, the Colorado River is arguably the most regulated and contested river in the United States.

The Colorado River is renowned for carving out iconic landscapes, including the Grand Canyon, a testament to its erosive power over millions of years. However, its significance extends far beyond its scenic beauty. The Colorado River is the lifeblood of the arid Southwest, providing water for agriculture, urban centers, and industries in seven states.

The demand for Colorado River water far exceeds its supply, leading to intense competition among states and Mexico. The Colorado River Compact of 1922, which allocated water rights among the states, has proven inadequate in the face of increasing population growth and climate change. Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the two largest reservoirs on the Colorado River, have shrunk dramatically in recent years, highlighting the severity of the water scarcity crisis. Innovative solutions, such as water conservation measures, drought-resistant agriculture, and desalination projects, are being explored to ensure the long-term sustainability of the Colorado River basin.

The Columbia: Powering the Pacific Northwest

The Columbia River, the largest river in the Pacific Northwest, stretches approximately 1,243 miles from its source in the Canadian Rockies to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean. The Columbia River basin encompasses portions of seven states and two Canadian provinces, playing a crucial role in the region’s economy and ecology.

The Columbia River has been extensively dammed for hydroelectric power generation, making it one of the most productive rivers in the world in terms of electricity production. The Grand Coulee Dam, one of the largest concrete structures in the world, and other dams along the Columbia provide a significant portion of the Pacific Northwest’s energy needs.

However, the dams have also had a devastating impact on salmon populations, which were once abundant in the Columbia River. Salmon rely on free-flowing rivers to migrate upstream to spawn, and the dams have obstructed their passage and altered their habitat. Efforts to restore salmon populations include fish ladders, hatchery programs, and dam removal projects. Balancing the need for hydropower with the imperative to protect endangered species remains a complex challenge for the Columbia River basin.

The Ohio: Gateway to the West and Industrial Hub

The Ohio River, formed by the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, flows approximately 981 miles to its confluence with the Mississippi River in Cairo, Illinois. The Ohio River served as a vital transportation route during the early westward expansion of the United States, earning it the nickname "Gateway to the West."

The Ohio River valley became a major industrial center in the 19th and 20th centuries, fueled by abundant coal resources and access to transportation via the river. Steel mills, chemical plants, and other industries lined the riverbanks, contributing to economic growth but also causing significant pollution.

Efforts to clean up the Ohio River have been underway for decades, with some success in reducing industrial discharge and improving water quality. However, challenges remain, including non-point source pollution from agricultural runoff and urban stormwater. The Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission (ORSANCO) plays a crucial role in coordinating pollution control efforts among the eight states that border the river.

Other Significant Rivers: Shaping Regional Landscapes and Economies

Beyond these major rivers, numerous other waterways contribute to the diversity and vitality of the United States. The Rio Grande, forming the border between the US and Mexico, is a critical water source for agriculture and urban areas in the arid Southwest. The Snake River, a major tributary of the Columbia, flows through the scenic landscapes of Idaho and Washington. The Potomac River, flowing through the nation’s capital, holds historical and symbolic significance. The Hudson River, connecting New York City to the interior, has played a crucial role in trade and transportation. The Susquehanna River, flowing through Pennsylvania and Maryland, provides water for agriculture and recreation.

Conclusion: Rivers as Reflections of a Nation

The major rivers of the United States are more than just waterways; they are integral to the nation’s history, economy, and environment. They have shaped the landscape, influenced settlement patterns, facilitated trade, and provided sustenance for generations. However, these rivers face significant challenges, including pollution, over-allocation of water resources, and the impacts of climate change.

Understanding the complex interplay between human activities and river ecosystems is crucial for ensuring the long-term sustainability of these vital resources. Balancing the competing demands of economic development, environmental protection, and recreational use requires careful planning, innovative solutions, and a commitment to collaboration among stakeholders. As the nation navigates the challenges of the 21st century, the health and vitality of its rivers will continue to be a reflection of its values and priorities. Studying the rivers map of the US is, in essence, studying the heart and soul of the nation itself.