J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion is more than just a prequel to The Lord of the Rings; it is a meticulously crafted cosmology, a rich and complex mythology encompassing the creation, fall, and eventual fate of Arda, the world in which Middle-earth resides. Central to understanding this epic narrative is the concept of place, and no understanding of place in Tolkien’s world is complete without considering the map. While Tolkien never created a single, definitive map for the entirety of The Silmarillion, the maps of Beleriand and later Middle-earth, particularly those accompanying The Lord of the Rings, serve as invaluable guides to navigating the vast landscapes and pivotal events that shape the history of the First Age and beyond. These maps are not merely decorative; they are integral to the storytelling, embodying the themes of loss, change, and the enduring power of the land itself.

The absence of a comprehensive Silmarillion map highlights the inherent incompleteness of the narrative. The Silmarillion, compiled and edited by Christopher Tolkien from his father’s extensive writings, represents a fragmented history, pieced together from various accounts and perspectives. This incomplete nature mirrors the fragmented state of Arda itself, marred by conflict and destruction, particularly the sinking of Beleriand. The existing maps, therefore, serve as snapshots, glimpses into specific periods and regions, leaving much to the imagination and emphasizing the vastness and unknowable depths of Tolkien’s creation.

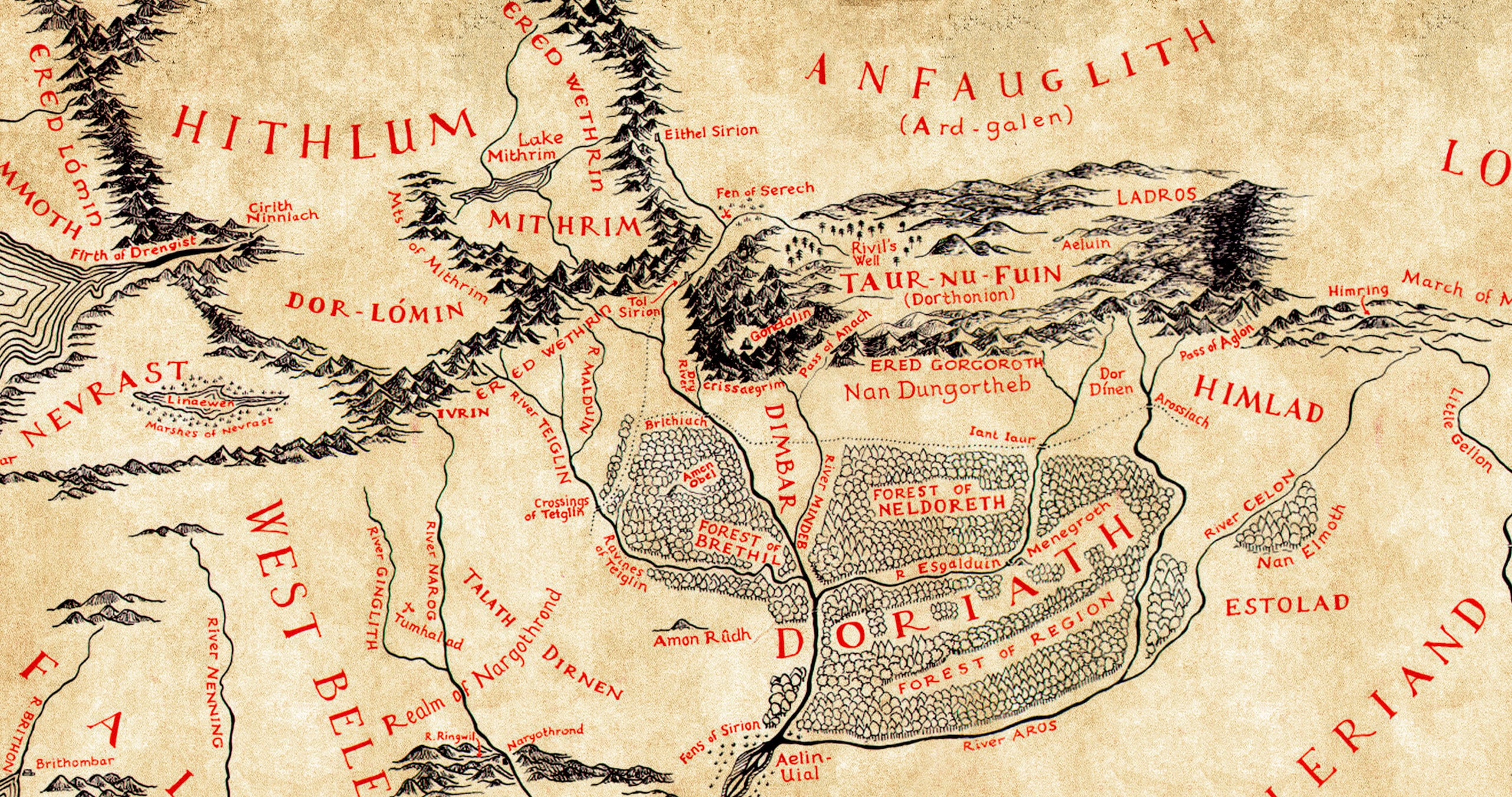

The most significant map associated with The Silmarillion is undoubtedly the map of Beleriand. This region, located to the west of Middle-earth, played host to the epic battles and tragic romances that define the First Age. Without a map, visualizing the geography of Beleriand would be a daunting task. Imagine trying to comprehend the strategic importance of passes like Aglon or the treacherous journey down the River Sirion without a visual aid. The map anchors the narrative, allowing readers to trace the movements of characters, understand the layout of kingdoms, and appreciate the strategic significance of key locations like Doriath, the hidden kingdom of Thingol and Melian, or Gondolin, the last bastion of the Noldor elves.

Consider the War of Wrath, the final, devastating conflict that brought an end to Morgoth’s reign in the First Age. The map of Beleriand allows us to grasp the scale of the destruction wrought by this war. The cataclysmic events that unfolded, culminating in the sinking of Beleriand beneath the waves, are brought into stark relief when we see the geographical context. We understand the magnitude of the loss, not just of lives, but of entire landscapes, cultures, and histories. The disappearance of Beleriand is a tangible representation of the irreversible changes that shape Arda, a testament to the destructive power of evil and the enduring impact of the past.

Furthermore, the map of Beleriand highlights the power of naming and the deep connection between language and place in Tolkien’s world. Each name on the map – Dorthonion, Ered Gorgoroth, Nan Dungortheb – carries a weight of history and meaning. These names evoke images of ancient forests, towering mountains, and perilous valleys, imbuing the landscape with a sense of mystery and foreboding. The intricate details of the map, from the meandering rivers to the carefully drawn mountain ranges, contribute to the overall sense of verisimilitude, making Beleriand feel like a real, albeit lost, place.

Beyond the map of Beleriand, the maps of Middle-earth, primarily those found in The Lord of the Rings, provide a crucial link to the events of the First Age. While Beleriand is gone, its influence permeates the landscape of Middle-earth in the Second and Third Ages. The remnants of the Blue Mountains, which once marked the eastern border of Beleriand, serve as a reminder of the cataclysm that reshaped the world. The locations of ancient battles, such as the Field of Celebrant, are steeped in the history of the First Age, even if their physical form has changed over time.

The maps of Middle-earth also allow us to trace the migrations and settlements of the Elves, Dwarves, and Men, descendants of those who lived and fought in Beleriand. We can follow the paths of the survivors who fled the destruction of Beleriand, seeking refuge in new lands and establishing new kingdoms. The map becomes a historical record, charting the movement of peoples and the evolution of cultures across vast stretches of time.

The significance of the map extends beyond mere geographical representation. It also serves as a symbol of hope and resilience. Despite the devastation and loss that pervade The Silmarillion, the map reminds us that life persists. The world may be scarred, but it is not broken. The descendants of those who fought against Morgoth continue to strive for good, and the beauty of the land endures, albeit diminished. The map, therefore, is not just a record of the past, but also a testament to the enduring spirit of those who inhabit Arda.

Moreover, the act of mapping itself can be seen as an act of defiance against the forces of entropy and decay. By charting the land and naming its features, the inhabitants of Arda attempt to impose order on a world constantly threatened by chaos. The map becomes a way of claiming ownership, of understanding and controlling the environment. In a world where history is constantly being rewritten by conflict and destruction, the map provides a sense of stability and continuity.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of these maps. They are, after all, human-made representations of a world that is far more complex and nuanced than any map can fully capture. They are subject to the biases and perspectives of their creators, and they inevitably simplify the intricate details of the landscape. However, these limitations do not diminish the value of the maps as tools for understanding The Silmarillion. On the contrary, they serve as a reminder that our understanding of Arda is always incomplete, always subject to interpretation and re-evaluation.

In conclusion, the map is an indispensable tool for navigating the vast and complex world of The Silmarillion. Whether it is the detailed map of Beleriand or the broader maps of Middle-earth, these visual aids provide a crucial framework for understanding the geography, history, and culture of Tolkien’s creation. The map is not merely a decorative element; it is an integral part of the storytelling, embodying the themes of loss, change, and the enduring power of the land itself. It allows us to trace the movements of characters, understand the strategic significance of key locations, and appreciate the scale of the epic events that shape the history of Arda. While the absence of a comprehensive Silmarillion map highlights the incomplete nature of the narrative, the existing maps serve as invaluable guides, inviting us to explore the depths of Tolkien’s imagination and discover the enduring magic of Middle-earth and its lost, legendary past. By studying these maps, we gain a deeper appreciation for the richness and complexity of Tolkien’s world, and we come to understand the profound connection between place, history, and identity in the tapestry of Arda.